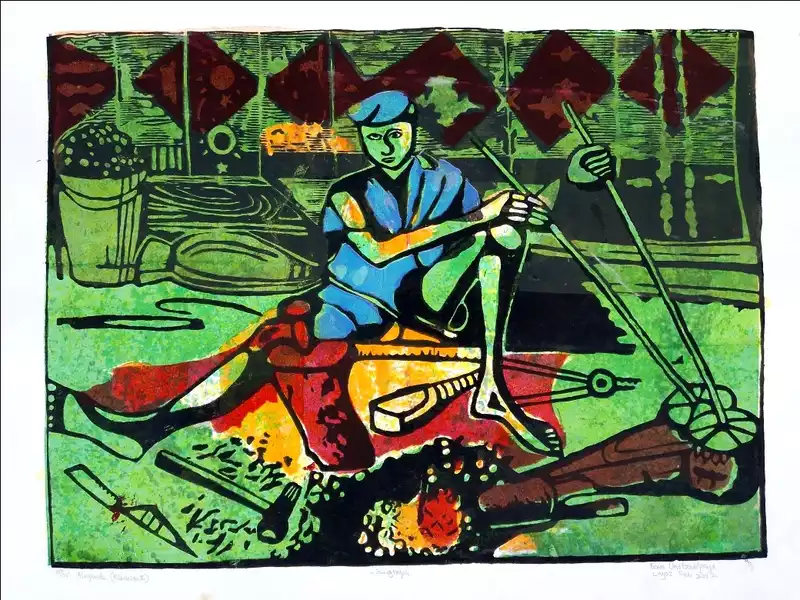

Tshepiso Moropa’s collages employ a range of archival imagery and materials to create visual dialogues about the past and present tense of black people, the African diaspora and historical archives. With an educational background in Psychology, Linguistics and Research, Moropa’s artistic journey has been marked by a deep passion for the medium and an unwavering commitment to storytelling through the art of collage. Through her hand-crafted work, she seeks to reawaken forgotten narratives to create a visual symphony that resonates with the depths of human experience. Tshepiso Moropa’s handcrafted collages use black-and-white archival imagery to enhance texture and light, breathing new life into old stories and inviting viewers to explore the deep intersections of history, symbolism, and personal interpretation.

Moropa has been part of numerous exhibitions including her first solo exhibition at Eclectica Contemporary gallery in Cape Town and featured in publications such as 1854. Photography and the South African newspaper The Mail and Guardian. She is the recipient of the CAP Prize Award 2024 and currently resides in Johannesburg, South Africa.

In a conversation with Omenai, Tshepiso Moropa talks about her Contemporary African Photography Prize win with her project, Dineelwane, her artistic process and her current interests.

First, I must say congratulations on winning the 2024 Contemporary African Photography Prize Award! How did the project, Dineelwane, come to life?

Tshepiso Moropa: Thank you! Winning the award was such a pleasant surprise for me. I was up against very strong photographers and contenders, so receiving it was definitely a humbling experience. In regards to Dineelwane, the work in itself is a personal project for me. Growing up, my mother and my aunt used to tell my sisters and me these frightening but exciting folktales and folklore that they heard growing up. I used to imagine each folktale as it was narrated to me. Fast forward to 2023, and I had to do an Instagram takeover for a photography collective that I am part of called The Photographic Collective, and the theme of the takeover was storytelling. My mind instantly took me to my childhood. I then used a SeTswana folktale that was in an academic research paper that I discovered as a guiding tool. I realized that there wasn’t enough artwork that pertains to folktales and folklore in SeTswana, and I think that made me realize how important this work was and how it can be used to spotlight not only SeTswana folktales but SeTswana authors as well. So that’s how Dineelwane came to be.

What first drew me to your work was the storytelling behind each collage, as well as the contemporary preservation of archival materials. How do you decide on the archival material to use in your work?

TM: I use archival images of black people from Africa in my work. I am drawn to photographs of people that look like me. I’ve always been intrigued by these images, and I also want to know more about them. Who were they? Where do they come from? What’s their story? There are some archival images that do have some sort of information about the people in them, but I am more drawn to the ones that have absolutely no information on them. I spend most of the time researching these images, and once I find an image that I am fascinated by or drawn to, I would store it in a folder to use in the future. Once I feel inspired to create a collage or film, and when I do have a folktale that matches that particular archival image, I use it. By repurposing them, I feel like I am preserving them in a way. I want to make sure that they are not forgotten because they are an important part of history and I do not want them to be erased in any sort of way.

What determines the subject matter you choose to explore?

TM: What determines the subject matter is the folktale I am inspired by. Most of the time, I go by feeling or imagination. Sometimes I just create a collage without any particular meaning and I only think about the meaning afterward. For the most part, I am drawn to family archival images. I always feel like those are open to interpretation, which I appreciate.

Working in photography, collage, and film, your art primarily explores themes of identity, family relations, violence, race, gender, love and sexuality, solitude, and the sense of belonging. I am curious about which medium came to you first. And what drew you to photography and collage as a medium?

TM: It started with photography, then collages, and then ultimately led to film. Funny enough, the medium I actually started with was painting. Apart from photography, collage and film, painting was the medium that I used to practice with until I received an internship to work at a photography school in 2019. I worked as a library assistant at a special library that housed both photography and theater books. It included so many photo books of photographers from South Africa and internationally that I had no idea of at first. I remember going through each book and being fascinated with the medium. It became my entire life. I think being surrounded by photographers made me want to take part in it as well. I used to take portrait photographs and then I moved to collages because it was easier to create with. Collages are more forgiving if you make a mistake. You can literally create an entire new world with collages and I think I like the flexibility.

Can you share how your educational background, which is in psychology, linguistics, and research, translates into your practice?

TM: Research is a huge part of my artistic practice. I don’t think my work would be where it is without it. Earlier I had mentioned that the series Dineelwane was inspired by a folktale found within an academic research paper. The research paper belonged to a Master’s candidate who had written about magic and mythical creatures found in SeTswana folktales many years ago. I stumbled across it when I was researching for my own linguistics paper. I did not get the chance to use it until the following year. That research paper is an incredible guiding tool within my work and I am grateful that I get to utilize it as much as I can. Research and language forms a huge part of my work. I would be nothing without it. It taught me a lot on where to get resources and materials for the collages and how to better utilize them. They are essentially the backbone of my work, together with my experiences. As for psychology, I am currently working on new pieces that are definitely inspired by that.

Dineelwane is said to be inspired by SeTswana folktales and folklore. Your intention with this project was to bridge the gap between the past and present while preserving the cultural heritage of the SeTswana people. Do you think you were able to do just that with the project? And what was your experience with creating new narratives that didn’t exactly exist?

TM: That’s a good question. I honestly think that there is so much to be done still. I am trying to preserve not only the cultural heritage of SeTswana people but also spotlight SeTswana literature and authors. Obviously that cannot be done with just one body of work but I am trying to make sure that that particular aspect transpires into newer work as well. It’s so important to hold onto that essence. I do not want to lose it while creating new work because it is an integral part of my work. It takes a lot of imagination to create new narratives that didn’t exist before. It also takes a lot of respect and consideration. I must say, there’s a thin line when it comes to repurposing archival materials. I realize that it’s more than just creating. It’s more than art. It involves a lot of people and history. It takes time and a lot of thinking because you don’t want to make the wrong move and offend anybody. But at the same time, it’s so important to utilize these materials the best way you can because you have to bring attention to them. You have to breathe new lives into them. If you don’t, people will ultimately forget about them.

What does your process of creating a new artwork look like?

TM: My artistic process differentiates from project to project. It depends on whether I am making a collage or film. With collages, it starts with research. Researching the folktale and researching the archival image, which is either from online or from my personal collection. Since I work with digital and traditional collages, I sort of “design” how the collage would look on my iPad before printing the images out. Once I am satisfied with the outcome, I print out the images and then create the traditional cut-and-paste collage. Designing them digitally allows me to edit the pieces so that the colors match and they flow properly on paper. Ultimately, I scan the collage, and that’s what you see as the final print. This typically takes me about a day or two to complete. Whereas with film, it’s all digital. The films are typically inspired by folktales. Once I have a folktale that I am inspired by, I create a storyboard for each scene. I then source all the images that I feel are appropriate for the film. My favorite part of the film process is making the music and sound effects. All the music you hear is composed and arranged by me. That consists of the first part of sound. The second part is the narration of the film. The voice that you hear is my mother’s. She typically narrates most of my films. By doing that, I try to capture the essence of an elder narrating folktales to children, like in my childhood. Once that is done, I create a collage for each scene. Some scenes require the stop-and-go process, and this can take quite some time, especially when the film has about 50 to 60 frames. Sometimes more. Once I feel like the collage process is done, I then move to the final part which is the editing and post-production process. This includes putting together all the scenes in chronological order plus adding the sound. This takes about a week to complete.

What are you working on now?

TM: Lately, I’ve been thinking about how to better present my work. I think I have outgrown the standard print-in-a-frame thing. I want to make work that the viewer can experience in a whole new way, so I’ve been looking into installation art. I am really interested in dioramas. I feel like they give a whole new meaning to storytelling. I am quite excited about that and cannot wait to see how my work will turn out.

Iyanuoluwa Adenle is a Nigerian art writer, essayist, and poet based in Lagos. She is currently the head writer at Omenai. Adenle has contributed to a number of art publications, including Tender Photo, Art News Africa, Pavillon 54, and Omenai.