Focusing on Black diaspora art, Sabo Kpade is pushing the boundaries of contemporary art by creating immersive experiences that challenge traditional boundaries and start thought-provoking conversations. Inspired by Okwui Enwezor’s work as a thinker and curator, Kpade’s multifaceted approach in his curatorial practice is rooted in collaboration and intellectual inquiry. At the Lagos Biennial 2024, he curated “Khalwa Room II”, an off-site and site-specific installation of Nigerian multidisciplinary artist Uthman Wahaab’s work.

Sabo Kpade is a writer, curator, and researcher who specialises in the arts and cultures of Africa and its diaspora in the UK, US, and Europe. He studied Global Arts and Cultures at the Rhode Island School of Design (US). His second masters is in the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas at the University of East Anglia (UK). Currently, he writes for Contemporary & and Apple Music. Previously, he wrote for Okay Africa, Guardian Newspaper Nigeria, and Media Diversified.

In a conversation with Omenai, Sabo Kpade talks about his curatorial practice, transitioning from art and music journalism to art curation, and Okwui Enwezor’s influence on the contemporary art scene.

How did you first become interested in curation?

Sabo Kpade: I started as an art writer. Before that, I was writing short stories and working on a novel manuscript. I reported on Afro-pop and art exhibitions in London for Okay Africa. My focus was on African diasporic artists. After a few years of writing until 2019, it seemed like time for a new challenge. I decided it was time to professionalise as I didn’t have a degree. I had dropped out of the Federal University Of Technology, Minna where I studied Geology. One way to professionalise, for me, meant getting a master’s. I decided to put all my journalism (art, music, theatre, literature) into a portfolio and submitted it to fourteen different art and culture study programs in the US. Added to my savings from my retail job in London, was generous support from Wally Bakare who runs Tilga Arts Fund, introduced to me by Hannah O’Leary, Head of African Art at Sotheby’s, and Kavita Chelleram, founder of Art House and kò Gallery, both in Lagos. A scholarship from RISD and support from the aforementioned names, among others, helped to facilitate this transition from reportage to curation.

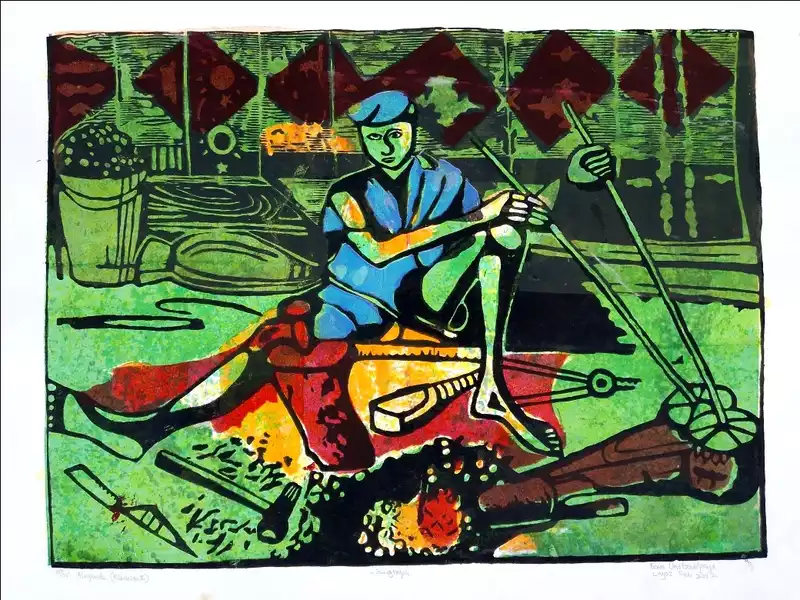

I was first at Retro Gallery in Abuja. It was important to sit and work in the gallery from morning till evening just to understand how things worked there. That was important for me; to just get a feel for it. When people came to see the show, what they liked, and their reaction to the exhibitions. That was good for like two months before I moved to kó Gallery in Lagos where I assisted Joseph Gergel, the director. kó gave me my first start as a curator and art writer. I had contributed to their exhibition catalogues but now I had the opportunity to curate two exhibitions concurrently: E.D Adegoke: The Age of Dreams and Busayo Lawal: Life in Asymmetry. Having moved from Kaduna to Lagos, kó made it easy by providing accommodation, and I lived just behind the gallery. I simply had to walk to work. These things mattered because then I could create and focus on work.

So Retro first, and after a long career in journalism in my section of things, I moved on to kó, RISD, and the University of East Anglia, while taking on the freelance work in art and music that came my way. Gradually, an area of interest, not a mission statement, started emerging for me in the visual arts of the Black Atlantic.

As a curator and a writer, what has the experience been like?

SK: It’s been rewarding—frankly. Once you figure out what the artist wants to do with the work, the process of thinking through an idea and bringing it to life begins. It applies to everything we do and it is very satisfying. Someone in tech asked me a question at a bar recently because it seemed like I was talking too much about art: “What is it about art that you like so much?” My answer was along the lines of always feeling very full after seeing a good show. I don’t feel a need for anything by way of a drink, a chat, or some company. There’s this satisfaction that I have that I don’t think is replicated elsewhere in my life. And I know by now, at this age, that it’s quite an important feeling or intuition to follow. Still an early career, still early days. There’s a lot more to come and I’m excited for it.

How does your own narrative as a writer and a journalist fit into your curatorial work?

SK: I came to intellectual life generally through fiction and journalism. As a writer, you understand it’s a way of organising and understanding your own world. Writing about art did even more. Intellectually, coming into curation by being a writer first was very helpful. It has the added advantage of properly explaining what the curator, as a writer, and the artist are trying to do. It is asking the artist you’re working with: “What are your abiding interests” and “What do you want to achieve?”. It’s a way of mapping out and explaining the world you want to present. So, writing and curating, in my case, are inseparable. It’s been incredibly valuable. And frankly, as a cheat mode, I knew that if I had people’s respect as a writer, they would let me put on a show. (laughs)

What kind of projects are you drawn to?

SK: I want to curate important shows. However, there is one’s interest, and there is what’s possible given any set of circumstances. A key part of curation for me is to always remember I am in service of the work.

Do you follow any particular curatorial theories or ideologies in your work?

SK: I did my second thesis on Enwezor’s work which I liked a lot because of the challenge in it which was to explore Guy Debord’s notion of spectacle through Enwezor’s curatorial career. The year before, I must have gone around RISD’s library taking down all of Enwezor’s essays in catalogues and essay collections. This was important for my own personal and intellectual background—to set aside a day or two to go around the library, take down every single book that had any of his essays in it, scan each one, and email it to myself. I didn’t think I would get the books in Lagos or Kaduna. I was the type of immigrant who would say: “Before I leave this country, I’ll take everything I need.” It took two work days of scanning and emailing. Why? Because by using Enwezor’s critical essays and exhibitions as a template, you wouldn’t have gone too far off the right path. I didn’t know what I was looking for till I found it. One key point he made in one text is “a drive towards the production of knowledge, not simply the production of an exhibition”.

How can curators work collaboratively with artists and communities for a more inclusive and diverse representation of African art in galleries, both locally and internationally?

SK: We can start by putting on the shows we want to put on, even with the limitations. Individually, independently. It’s hard work but it’s not impossible work. And I want to manifest of those ideas—I’ll call it a thesis—in the near future. Maybe one way for us to do that, as early-career curators, is to think long-term about our independent projects. Then there are different ways you can scale that up. For instance, The Artists Commune in Lagos is a loose-knit community of artists making works in different mediums and not limited to commercial galleries in Lagos. They are clued on and they make good work. An emerging curator can go to a space like that, introduce a curatorial idea, and articulate what they are trying to do.

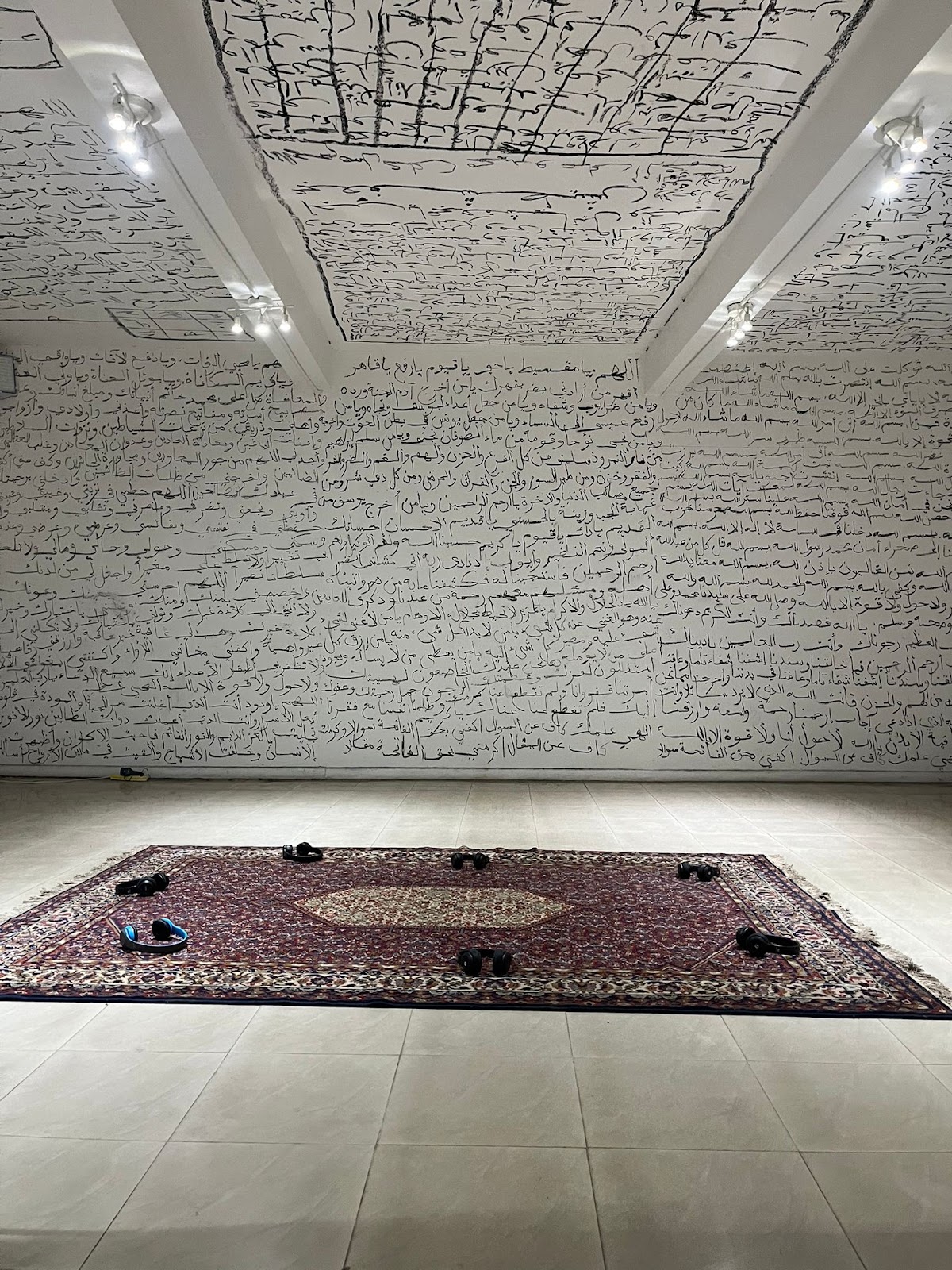

In collaboration with the Lagos Biennial 2024, you curated Uthman Wahaab’s current exhibition, titled ‘Khalwa Room II’ (2024), which was shown at the National Museum of Lagos. Could you tell me more about the work and the curatorial concept behind it?

SK: There was a 2012 British Museum show Hajj: Journey to the Heart of Islam which blew my mind with its sheer scale, breadth, and ambition. Its focus was the mass migration of Muslims to Mecca from the world over. Personally, it provided a template for how I could someday explore my familiarity with Islam in Nigeria, having spent the first half of my life in Kaduna, and my obsession with art making and art histories. Uthman Wahaab’s exhibition presented an opportunity to explore all these long-term interests, and of course, the opportunity to realise Wahaab’s interests in Sufi beliefs and various media. It was an exciting challenge to take on. Art and religion; that’s as old as anything. My role once again was to make it bloom. To help bring his compelling preoccupations to full flowering. It presented an interesting philosophical question for me in Uthman’s work: this idea of impermanence, especially when a major part of the work which was the Islamic calligraphy drawn all over the exhibition walls and ceiling, and was meant to be washed away by the artist in a private performance at the end of the show.

Can you name three curators and art writers you think the world should be on the lookout for? Why?

SK: I’ll say writer and critic Emmanuel Iduma, Peter Okotor at CCA Lagos, and Abuja-based Aisha Aliyu-Bima are impressive. As is Cuban-American Rey Londres, whom I met at Rhode Island School of Design, and who co-curated the first black biennial at RISD.

I am curating a guide of sorts. Please share one or two book recommendations that guide and inspire your practice as a curator.

SK: I will go back to Okwui Enwezor. It’s because he was always collaborating. He worked in collaboration with some of our most impressive intellectuals. Some of his writings exist as catalogue entries or as articles in journals, but to isolate one or two books he wrote, it would be Contemporary African Art since 1980 which he co-wrote with Chika Okeke-Agulu, Professor of Art at Princeton. The other is Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art. It’s published by Duke Press and it was founded by Enwezor, Salah Hassan, and Chika Okeke-Agulu. The main argument for starting Nka in the first place was that people wanted to talk about African art and curate African art. There wasn’t anywhere to go for text so they created a journal to answer that question. Okwui Enwezor, Salah Hassan, Chika Okeke, and Olu Oguibe are a small set of writers who championed contemporary African art in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

What are you working on right now?

SK: I borrow from Okeke-Agulu. When asked the same question, his response often is “nothing”. I’m working on nothing.

Iyanuoluwa Adenle is a Nigerian art writer, essayist, and poet based in Lagos. She is currently the head writer at Omenai. Adenle has contributed to a number of art publications, including Tender Photo, Art News Africa, Pavillon 54, and Omenai.