On Artistic Curiosities and the Shifting Nature of Value: In Conversation with Yaw Owusu

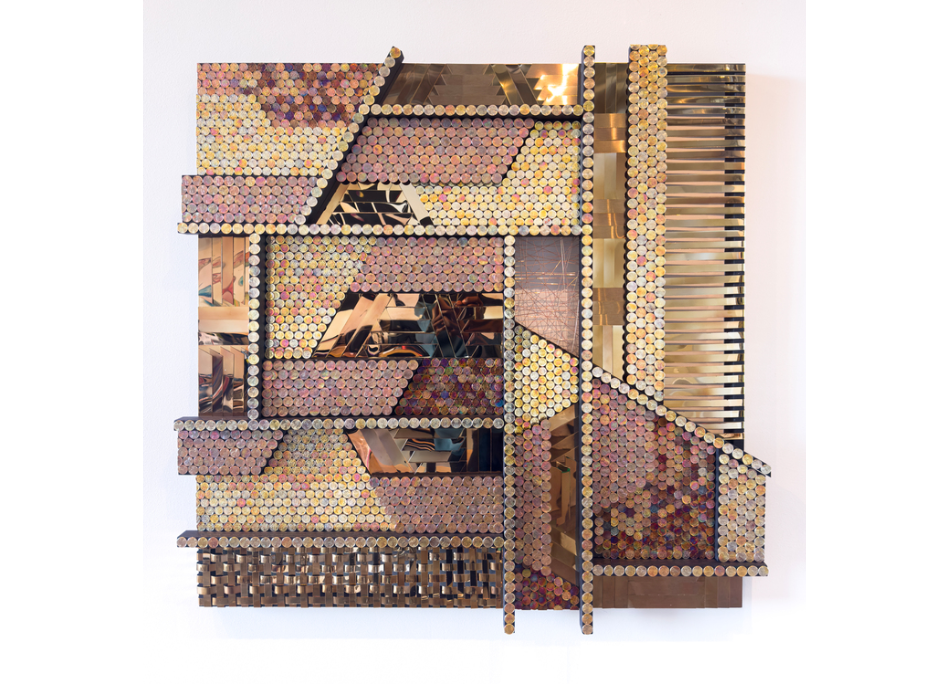

Beyond the aesthetic of beauty and the exploration of reuse and transformation, Yaw Owusu is an artist experimenting with ideas and objects, as well as form and space. In his continued investigations of value, his work often manifests as sculptural objects, paintings, installations, and social engagements. His curiosities, heavily based on the shifting nature of value itself, have extended to natural and chemical experimentations, therefore leading to the creation of more aesthetically pleasing works and an understanding of how value works politically, economically, and beyond borders.

Born in Kumasi (b. 1992) Ghanaian artist Yaw Owusu is known for his sculptural installations created from the dematerialization of found objects. He received a BFA from Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), the influential research-led and innovative art institution, where he studied sculpture and painting before moving to New York to pursue a Master’s in fine arts at the renowned Pratt Institute of Art.

In a conversation with Omenai, Yaw Owusu takes us through his interest in the complex concept of value, how his curiosities serve as a focal point in his investigations of the shifting nature of value, and his ongoing project.

How would you describe yourself and your work?

Yaw Owusu: Well, I guess first off, I’m an artist. To the stretch of the word, in a way that I experiment with ideas and objects, as well as form and space. My work often manifests as sculptural objects, painted objects, and installations. Other times, they are social engagements. It ranges from the idea of an artwork in itself to actually making something that is physical as well. Who I am and what I do is inseparable in a way that the work is purely out of my curiosity about what value is and how you can create value. When I encountered the one pesewa in Ghana, which was the least of our currencies, my interest was piqued. Even though it was still a legal tender, the copper coin had lost its value to the point that it couldn’t be exchanged for anything. That encounter made me think, “Wow, what is money?”, “What is value?” And that began my journey.

Can you expand on your journey as an artist who is fascinated with the concept of value?

YO: When I did a project in the coastal area of Ghana, it was for a pinhole camera project. I realized that the coins that I had, which were copper, had reacted to the seawater because they’re very fragile texture-wise. The political and economic side of it was more relevant than just making aesthetic objects out of it. Then I was making installations and works that questioned these areas of sovereignty, independence, or value, be it governmental, social, or economic when I was in Ghana. Since then, I have traveled to New York, Tijuana, Mexico, and Dubai, and my work has evolved from the use of the Ghanaian pesawa to US pennies to Pay cards when the minimum wage increased in the US. My work has evolved from just the object to the idea. From experimenting with natural and chemical processes to get color and texture, to trying to get an understanding of how things work economically and politically, which is where my research is, the work has taken me to the idea of place and how it adds or takes away value. When I bring the Ghana pesewa here, it’s worthless. Same as when I take the US penny to the UAE, it’s useless. So, how a place or the idea of place affects what value is has become also very interesting.

What’s your educational background? And do you think that it influenced your artistic practice?

YO: I hope so, but it did. I studied Arts in high school. I also did picture-making, which was like creative arts. I did BFA Painting and Sculpture/Fine Arts in my undergrad. I also did Arts for my Master’s degree. I have some sort of interest in Chemistry and Elective Math, so I guess that kind of influenced my practice a little bit. At some point, I got into the Architecture program at Pratt but I dropped out.

What does your artistic and creative process look like?

YO: Well, it starts with the experimentation and then research. Since I almost seized myself from using paint in any form, which could have been easier, I’m kind of taxed to create color by itself. So, it’s just experimenting with other solvents and other conditions so I can get the colors and textures that I want. It is more than repeating or creating aesthetically pleasing images. It is me asking questions like, “Why am I using this?” This is why I started a conversation about how each work is created. These bodies of work are based on historical, political, and economic queries. Then the research cements the whole idea and forms a base of dialogue, perhaps of revelation, and then engagement as well. The research also shows in the structural form of looking at things that are close to me, things that I see all the time. Like in Ghana, the works had a more vertical composition in their creation and this is because Ghana has shorter buildings, therefore the work was dispersed instead of raised. While in New York, my windows are vertical and tall and that also affects the work greatly. I didn’t understand it until I saw the difference when I looked at old works and compared them to the new ones. I realized what was happening subconsciously, and it just had to do with the idea of me shifting spaces. All of these play a role in how the work manifests itself and how I create.

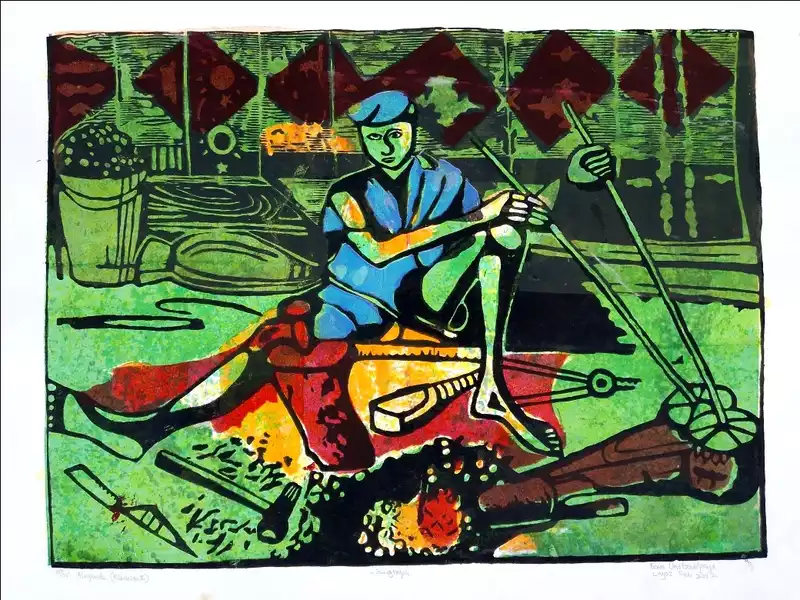

I understand that you started from traditional painting of political figures, popular culture, and royalty to sculptural installations that incorporate found objects like steel, gold, silver, and copper in your investigation of the concept of value. How did you arrive at this medium and how has it contributed to your practice?

YO: My works are real experiences. Having grown up and seeing my dad engage in dialogues around politics and literature influenced my interest in painting political figures, popular culture, and royalty, and now, exploring the concept of value. It also influenced my curiosity about how systems work. For instance, living in New York and seeing how the spaces were more vertical in their composition had an impact on how the work was done. It contributed to how I try to make sense of these subjects or facts and where they fit perfectly in my practice. When I’m in Ghana, I’m privy to these cultural elements and political realities because I was born and raised there. These experiences form the conversation, even in the form of the work and the materials used.

Your process of dematerializing found steel, gold, silver, and copper with various natural and chemical treatments like salt and vinegar, is an experimentation to evoke age and wear. Can you expand on your current curiosities and experiments?

YO: I have decided not to do any solo shows this year because, in the last five years, I’ve done different kinds of research-based solo projects and I want to take the time off to push the work to a different dimension and try new forms. The idea is to engage with space much more than the objects. This began in 2020 when I did work in public spaces on my own. So this year, the project that I’m working on involves changing 100,000 pennies into gold and then putting them back into the system so it circulates the country. For now, I don’t know what it is for, but the whole idea is just to experiment with the idea of value. The original color of the pennies is copper, but what if it was gold-colored? What does it mean? What if it’s just 100,000 out of the billions of pennies that were created? What kind of value is being created? And by recirculating them, what is the validation of that currency? Is it accepted? Will people keep them, or would they trade with them? That’s the beginning of the work that I’m doing this year although I’m still in the process of making them. I’ll distribute them in different states, New York, Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C. Just like Washington, these three states have mints where they produce money so, it’s interesting to put that in these centers. I’ll see if I can add a fourth state, but I can start with these three. I love it when the idea of the work moves from creating an aesthetic object to just creating a kind of conceptual piece. I’ll work on installations like that for the whole year and next year, God willing, I’ll have a solo presentation to show the findings of this research.

How do you intend to recirculate these coins?

YO: There are different ways to distribute these gold-colored coins. I can take them back to the bank or dump them into coin sorters. When you dump them into these machines, you get a receipt so you can get the value of the money back and then the bank will recirculate that. I aim to mix the colored coins with a bunch of other collections in the machine. Rolling them would have been ideal but it won’t be as random as mixing them with regular pennies. Anybody could get it. They could end up anywhere; I could even get some back but the main goal of the experiment is to see if, by the time I change the color of these pennies, maybe people will still be able to use them. That’s my whole curiosity. I’m interested in knowing that. What does that become? I wouldn’t know until I did it. I can’t wait to find out. I’m throwing away money. It’s not a lot of money, but it’s still money. It’s like I’m making that investment, so I don’t want to predict how it will go. Who knows? Maybe they’ll say, “Oh, now turn all the coins into gold for us.” We want to introduce new gold pennies. I want to just do it. See the reaction. Also, it would be interesting to encounter them in circulation and see how people interact with the objects. Hopefully, if I ever get some back, I will document it.

What are the central themes you continue to explore in your work?

YO: My curiosity is heavily based on value itself. I guess it started as an alchemic curiosity, then experimentation. I’m still curious about the political connotations as changing money is like defacing it and that has political implications. Just as circulating bleached currencies have economic implications. These are central themes that I continue to explore in my work as I make these kinds of alchemic reactions. The whole idea is just trying to understand how money or value is actually made, and how people living in a very capitalist country create money.

Are there any artists, living or dead, that influence the style and techniques you work with?

YO: I’m still trying to find myself as an artist. I admire a lot of artists and I have learned from their ambitions and their curiosities as well. However, I just don’t think that I’m influenced directly by another artist. David Hammons’s African-American flag is one work I look up and Hammons is an artist that I respect for his process and his thought process. There are also colleagues that I respect for how they interpret their work. I have learned about the multiplicity of ways to express oneself. I’m spending so much time trying to create mine that I don’t have the room to be influenced by another artist.

As a Ghanaian artist living and working in New York and Accra who is fascinated by the history of a place and its people, what are some of the challenges you have encountered in your practice, and how have you been able to navigate them?

YO: Well, I’m still trying to navigate them. (laughs) But I would say that I am an artist and I am Ghanaian. I am Ghanaian by virtue of my heritage. Being born to a Ghanaian parent in Ghana makes me a Ghanaian. I’m an artist because of my curiosity about what I do and what I can hold. When I’m in New York, I’m an artist. I’m very sensitive to whatever is happening around me and how that affects me almost directly, the work, or people or things that I’m interested in. Whether I’m in Ghana, in the Middle East, in Europe, or in the US, I become just a person or an artist, following their curiosities. That kind of alienation also kind of informs the work because then, if you’re in Europe, you are categorized in certain ways, like political regard, or your expectations, responsibilities, and even limits. Those are things that I’m very sensitive to and how that affects the work. I look forward to ways that I can use that to make new work.

What are some of your non-negotiables in your practice?

YO: The ultimate thing that I strive for is integrity and that manifests as me doing my due diligence in terms of research. Being responsible for the work is also something that I strive for as I try to learn from my work. I don’t come to the studio with a sketch of the next thing to work on, I just show up and let the blank canvases of boards tell me how they want to be done. In the studio, the work itself guides the process.

Iyanuoluwa Adenle is a Nigerian art writer, essayist, and poet based in Lagos. She is currently the head writer at Omenai. Adenle has contributed to a number of art publications, including Tender Photo, Art News Africa, Pavillon 54, and Omenai.