In Lebohang Kangye’s multiple explorations of memory and history, she moves from a literal translation of her familial and interpersonal history using sculptural, performative, theatrical, and moving images to a more conceptual approach as she experiments with dimensionality. Her artistic restlessness is apparent in her latest dual exhibition, “The Sea is History” and “Mmoloki wa Mehopolo: Breaking Bread with the Wanderer” which is currently showing on the historic grounds of Boschendal Werf and inside the Manor House, respectively.

Born in Katlehong, Lebohang Kganye (b.1990) is a South African artist working with photography, sculpture, and film. Her practice is centered around her interest in memory and language. Kganye is experimenting with history, using her family’s old photographs, and incorporating personal archives and performance into a practice that centers storytelling and memory as it unfolds in the familial experience.

In her latest dual exhibition, “The Sea is History” and “Mmoloki wa Mehopolo: Breaking Bread with the Wanderer”, Lebohang Kganye raises profound questions about heritage, migration, and family archives. Her recent focus is on dimensionality, which has inspired her experiments with three-dimensionality as a means of seeing the world as an illusion. The four large-scale pop-up sculptures that make up ‘Mmoloki wa Mehopolo: Breaking Bread with the Wanderer,’ were built from scanned family photo albums and then printed out on a large scale.

In a conversation with Omenai, Lebohang Kganye talks about her preoccupation with memories, what drives her current experimentations with three-dimensionality, and her dual exhibition at Boschendal Werf.

How would you describe yourself and your work?

Lebohang Kganye: I am an artist whose archival inquiry is centered around oral histories through the use of existing images and narratives to implicate lesser-known subjectivities. My practice reflects on the construct of time in photography and memory. I am preoccupied with the act of remembering and the construction of memories through photography, the materiality of memory, and memories as a field of invention. This is indicative of my primary use of photography as a malleable medium, as well as my ongoing interest in the very construct of memory.

What does your artistic and creative process look like?

LK: My artistic process is mostly research-intensive and investigates the materiality of photography and the relationship between memory and fantasy. By positioning the “non-fictional” assumption of photography in conversation with the “fictional” world-building capacity of theatre and literature, though I mostly work with photography, film, and sculpture, I am often borrowing elements from theatre and literature. Therefore, lighting, staging, performance, and storytelling are key to my experimentations.

How did you arrive at dimensionality as a medium, and how has it contributed to your practice and your current body of work?

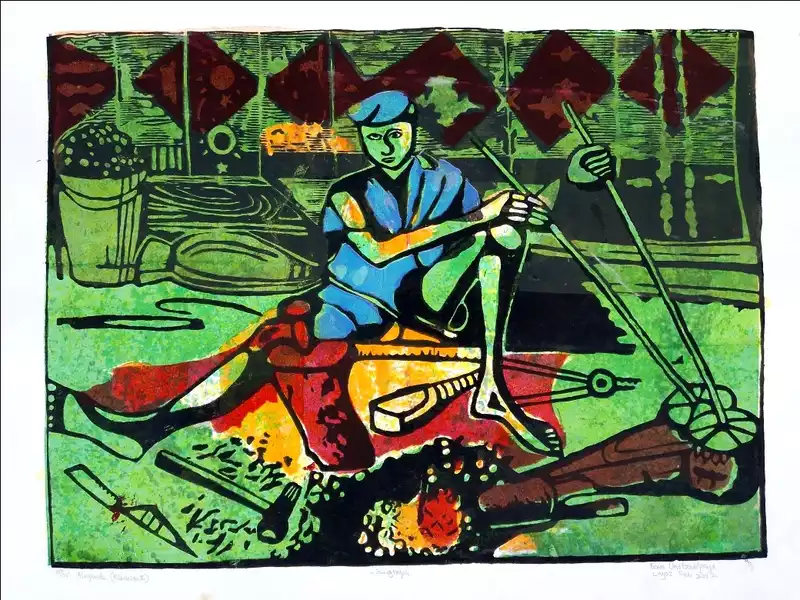

LK: After my photography studies in 2011, I worked for television productions as a photographer on set and became fascinated with the world-building possibilities of set design. When I started working on Ke Lefa Laka: Heir-Story (2013), where I portrayed my family’s narrative of the past through the story of my grandfather’s journey to Johannesburg, to create each scene, I turned architectural elements borrowed from the Internet and portraits taken from my old family photo albums into a theatre set. Printing them in black and white on large cardboard pieces and using them as the actors in my theatre set as life-size installations. The scenes created were based on oral stories told by my family members, passed down from one generation to the next.

Over the 12 years, the work has evolved and I have continued to experiment with different scales and materialities. The work Staging Memories (2022), makes use of literature as primary source material. Blending photography, theatre, and literature, Staging Memories (2022) presents the impact of the bigger picture on the small personal family and suggests contemplation of the way we construct and describe our memories. This work is presented in the form of a large-scale mechanized pop-up book installation and positions the “non-fictional” assumption of photography in conversation with the “fictional” world-building capacity of theatre and literature.

What are some of the challenges you have faced as you experiment with dimensionality in your work and how have you been able to navigate them?

LK: The more intricate some of the work becomes, such as the outdoor large-scale sculptures currently showing at Boschendal Wine Estate “The Sea is History”, it requires a different level of “collaboration” or rather the commissioning of different expertise – designers, technicians, engineers, etc. This is both exciting and challenging as it requires so many components to “seamlessly” go together, often times than not, the “mistakes” yield interesting results.

In your exploration of your familial and interpersonal history in “The Sea is History” and “Mmoloki wa Mehopolo: Breaking Bread with the Wanderer”, I notice an artistic restlessness. What questions do you seek to answer in your current investigations?

LK: “The Sea is History” stems from my recent curiosity about lighthouses, which became the basis for my multi-channel film installation, Dipina tsa Kganya (2021). The word dipina means ‘songs’ in my mother tongue, seSotho. The song referred to is that of my family clan names, traditionally passed down through oral tradition. Additionally, the Sotho word for ‘light’: kganya–is in the etymology of my last name: Kganye. The two performative gestures in the film are in conversation with the southern African practice of the ‘praise-singing’ of clan names as a way of passing down the origins of the family story as an act of resistance to historical erasure, to insure its unwritten continuity.

In the work that followed a few years later Keep the Light Faithfully (2022), I stage the tales shared by seven lighthouse keepers, previously and currently in service, living in some of the most isolated parts of South Africa – along the Western, Northern and Eastern Cape coastlines. In both of these works, I re-imagine the history of the rarely known and gendered narratives of hundreds of light keepers from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and the impact of labour on family structures.

“Mmoloki wa Mehopolo: Breaking Bread with the Wanderer” features a selection from a decade’s worth of work from five diverse projects and interdisciplinary approaches, the exhibition includes photography, fabric patchworks, and dioramas with scenography. Both offerings deconstruct the colonial context of the archival images and situate their meaning in a contemporary interrogation of the authorship of historical narratives.

Iyanuoluwa Adenle is a Nigerian art writer, essayist, and poet based in Lagos. She is currently the head writer at Omenai. Adenle has contributed to a number of art publications, including Tender Photo, Art News Africa, Pavillon 54, and Omenai.