There is no dismissing the role that curators and gallerists have played in democratising the art scene in recent years. With a focus on African art, democratising the art world means levelling the barriers that have made it difficult for African artists to make a career while working on their craft, and acknowledging the need for an equitable and diverse art market.

Courtesy of Red Heritage and Samuel Ajobiewe

In her lifetime, Bisi Silva relished her role as a curator linking African artists, and their work, to the public. Also known as “the godmother of contemporary African art,” Silva made conscious and practical efforts to democratise and bridge the gaps in the international art world as she discovered and promoted emerging, established or overlooked African artists to the world. Her observations of the jarring gaps in the art education system in the African art space inspired her to start the Asiko Art School. Here, she held a series of pop-up schools annually and hosted month-long educational events in various African countries where artists, writers, historians, curators and teachers immersed themselves in seminars, workshops and exhibitions.

Following Silva’s demise, associate curator at The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Oluremi C. Onabanjo wrote that “her remarkable vision and indefatigable spirit instigated tectonic shifts in editorial, curatorial and institutional frameworks in Nigeria and across the African continent” as she highlighted the range of work that came out of Silva’s non-profit art gallery, Center for Contemporary Art, Lagos. To date, C.C.A Lagos continues to expand on her legacy under the direction of Oyindamola Fakeye.

To democratise African art, curators, gallerists, collectors and other art professionals have to create more opportunities for African artists to exhibit their work on an international stage. How can we make the art world more accessible and inclusive? What part do art professionals – curators, gallerists and collectors – play in shaping the global perception of contemporary African art?

With Gallery 1957, Marwan Zahkem has been exhibiting inclusive and diverse works from boundary-breaking artists at international art fairs. The Lebanese-British gallerist has been intentional in his support of African artists. His plan has always been to ensure that artists have sustainable careers with the necessary resources and platforms at their disposal. This has led to the facilitation of many initiatives like the Yaa Asantewaa Prize and the gallery’s residency program, so artists can focus on their craft for up to a year.

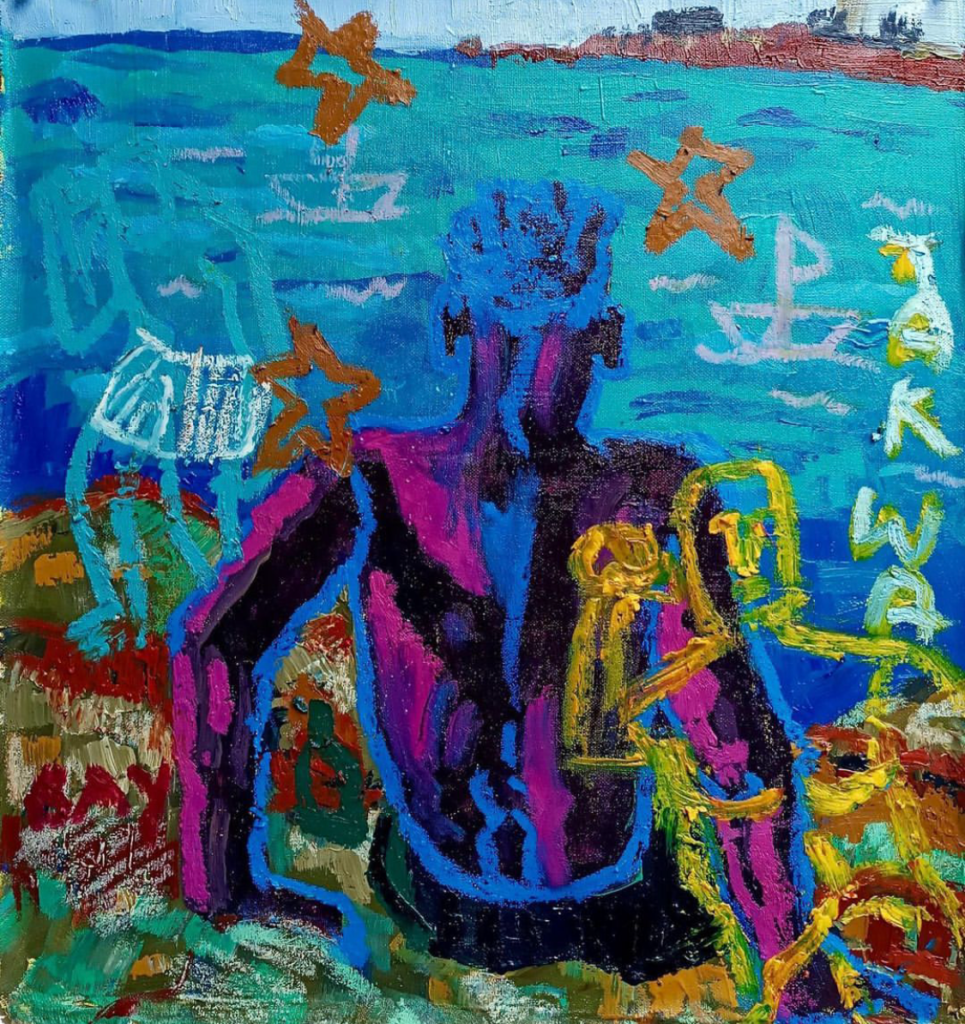

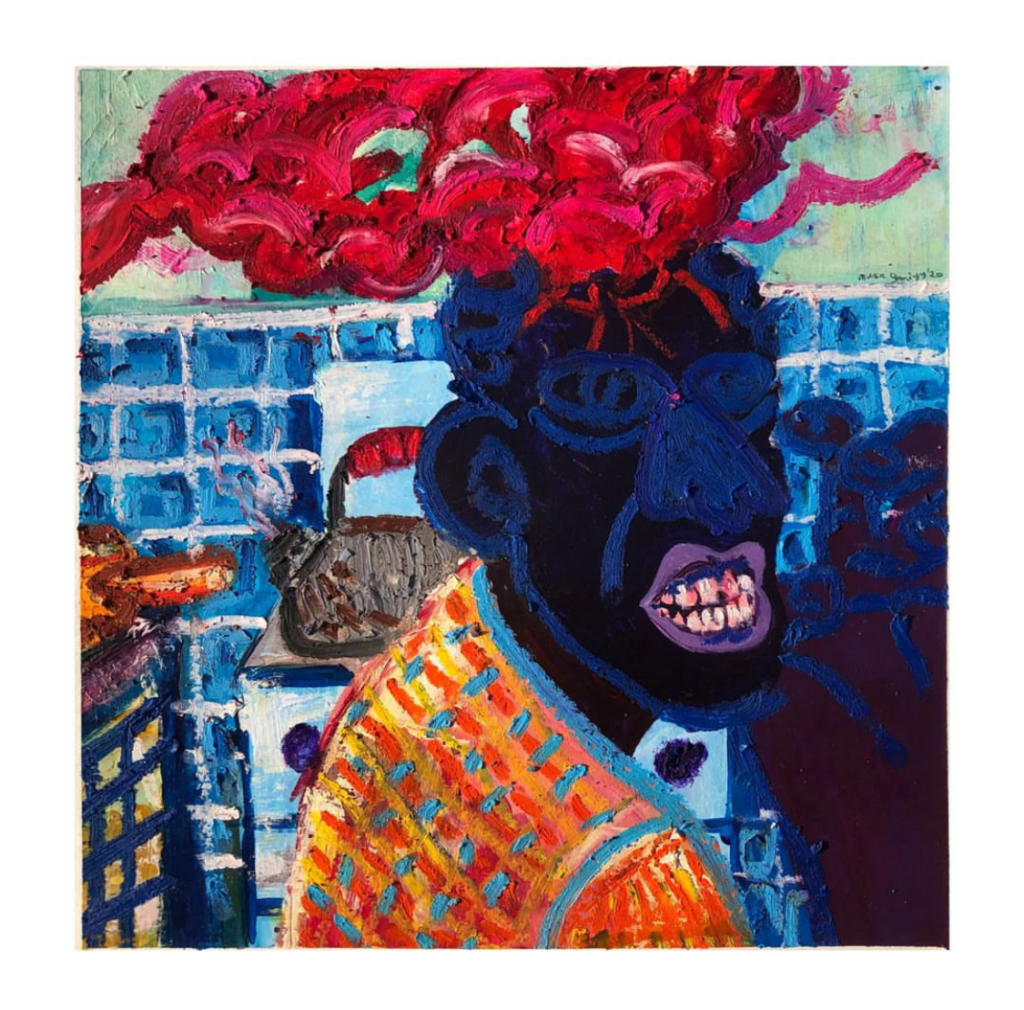

Courtesy of the artist

On the importance of the democratisation of the African art world to Musa Ganiyy as a visual artist, he says, “Democratising the business of African art has allowed me the opportunity to exhibit in Ghana and Ivory Coast. I’ve had the opportunity to be a resident artist in Grand Bassam, Ivory Coast alongside Nigerian, British and Senegalese artists. That experience has had an immense impact on my growth as a person and artist. I believe that the representation of African artists in the global scene is increasing as we are seeing more African galleries participating in international art fairs and festivals. Now, artists no longer have to settle for the bare minimum with regard to how galleries approach and offer exhibition contracts to them. This does not mean that there is still no gap between artists and collectors in the industry. Hopefully, more platforms can be created for artists to showcase their works to the world.”

Tony Agbapuonwu, curator and founder of Art Bridge Project, refers to art institutions as tastemakers. “I believe collectors, curators, and art institutions play an important role in shaping the global perception of contemporary African art as they are stakeholders in the ecosystem, and in the society, they are perceived as tastemakers,” he says. “Curators introduce artists to art institutions. The art institution provides space to show and nourish the artist which connects them to collectors and the general public. It’s like a food chain cycle and these stakeholders shape the perception of what is defined as contemporary African art. This is why curators, collectors and art institutions should endeavour to support the practice of both emerging and established artists, rather than focusing on trending artists or art styles.”

African artists can benefit from resources and assistance, such as grants, mentorship programs, and access to art school, which can help them advance their careers and develop their artistic skills. With technology, more art spaces with fair and transparent access for African artists can be created. The gap between artists and art collectors becomes even more slim as art can be sold and purchased with none of the usual difficulties.

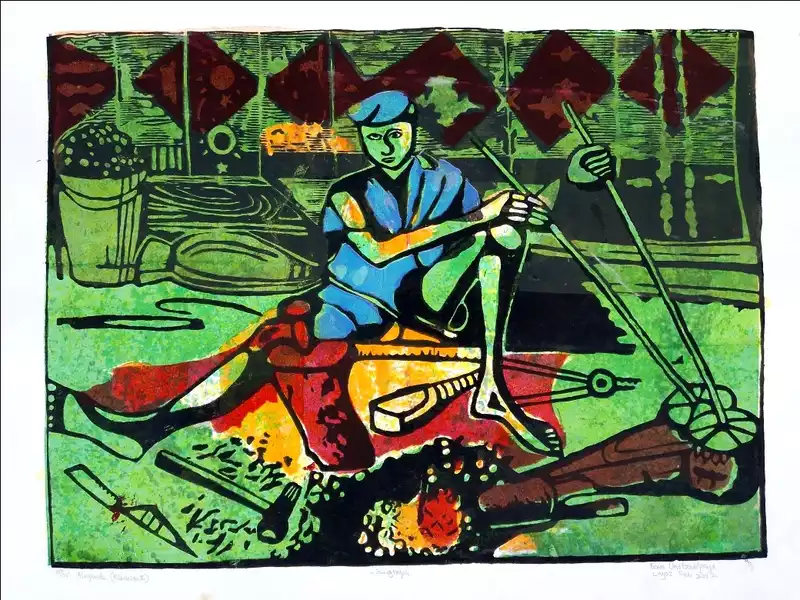

Courtesy of the artist

“In the age of technology and artistic freedom, art stakeholders should actively create space for experimentation where artists working with frontier mediums and techniques such as performance art, digital art, sound art, and abstract art can test out ideas and engage with new audiences,” Agbapuonwu says. “It is what actually drives my curatorial projects, I am always on the lookout and championing artists who embrace a more unique approach in their artistic creation focusing on crucially overlooked artists. Also, for a more accessible and inclusive perception of contemporary African art, we need more spaces beyond commercial institutions and spaces where artists can develop ideas, get grants for ambitious projects and nourish their practice.”

I believe that at the core of an ideal art scene is community and collaboration. An ideal art scene values inclusivity, diversity, and social responsibility. Curators, collectors, critics, gallerists, and artists need to work together. Artists with no writing skills can outsource the writing of their bios and artist statements to art writers so they can focus on their art. Older artists can start mentorship programs for emerging artists. Curators can focus on exhibiting, marketing and connecting artists to grants and mentorship programs that can make their work even more profitable in the future. Collectors can personally invest in artists that they enjoy their work, and galleries can invite more art critics to give honest feedback on an exhibition or an artist.

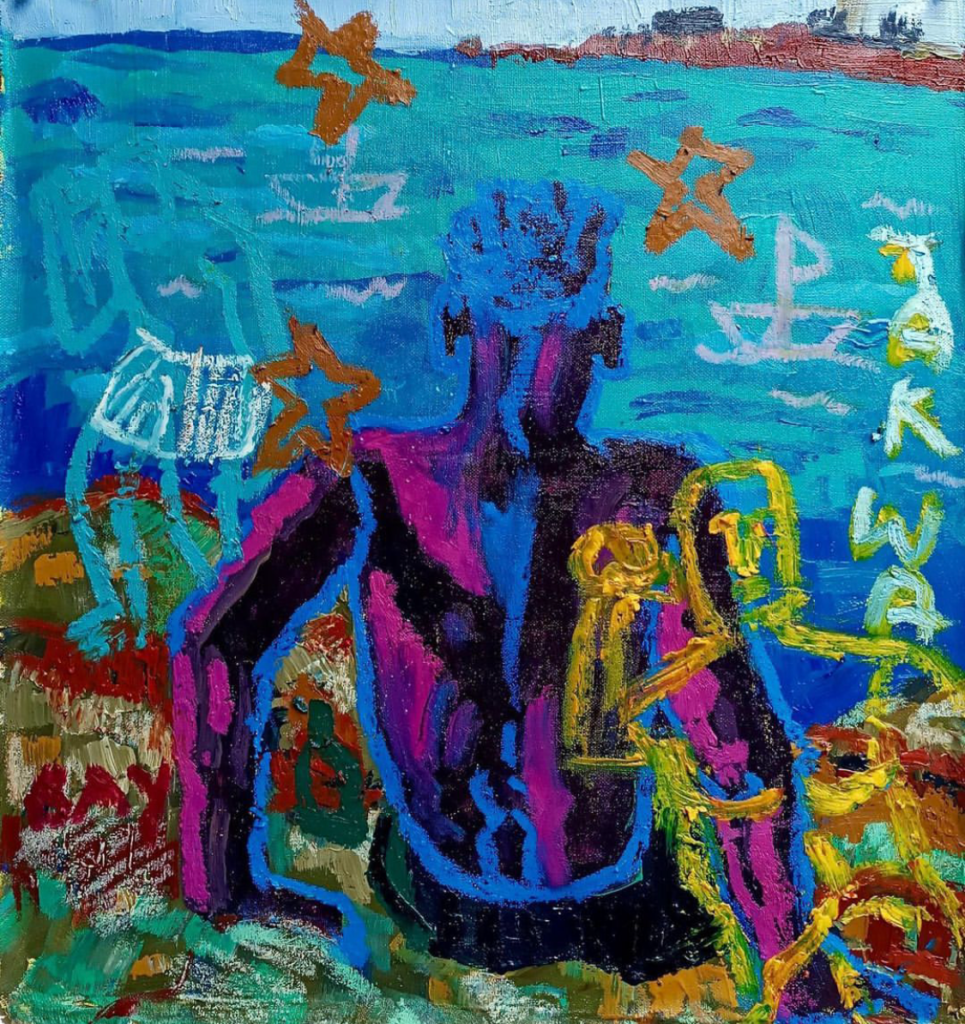

Courtesy of Art Bridge Project

Art education is another way of democratising and making the art scene inclusive, and just as Bisi Silva’s practice of engaging with the artist’s work in order to connect them with the global scene, Agbapuonwu says, “I strongly believe in the power of non-formal art education initiatives, workshops, laboratories, and residencies to transform the global perception of contemporary African art by radically empowering the artists and equipping them with new knowledge and the practicality of stretching the breadth of their practice.”

Iyanuoluwa Adenle is a Nigerian art writer, essayist, and poet based in Lagos. She is currently the head writer at Omenai. Adenle has contributed to a number of art publications, including Tender Photo, Art News Africa, Pavillon 54, and Omenai.